|

In the first decade of the 20th century Norwalk was a city on the rise. It's status as the county seat, two railroads, thriving manufacturing and business sectors, a population of more than 10,000, and the rapid transportation of electric interurbans, made for a prosperous present and promised an even brighter future. The citizens of Norwalk could not be faulted if they believed their town would one day rival larger neighbors such as Sandusky and Lorain. In early 1901, a giant new steel mill was planned for Norwalk. Rumors flourished for months regarding who was behind the project and where it would be located. In December, the Norwalk Steel & Iron Company was incorporated to manufacture high grade tool steel at a site north of town, along the W&LE railroad and Milan Ave. Construction of the plant began in the spring of 1902, and the first run of metal was produced in March 1903. But life in Norwalk was not entirely occupational; recreational opportunities abounded. For years the SM&N had offered easy transportation to Sandusky's waterfront, where passengers boarded steamships for the renowned Lake Erie resort of Cedar Point. Just east of town, at LSE stop 177½, was the picturesque retreat of Willow Brook Park, so named for the creek which had been dammed to create a small lake. A large, two-story pavilion provided space for dancing and parties, while a baseball field was used regularly by local teams and competitors from other towns. Farther east was the popular picnic grove of Ruggles Beach (stop 150), and the cottage resort of Mitiwanga (stop 149), which was founded by Norwalk clergyman Charles Aves in 1902. The theaters of Cleveland were quite popular as well, and the LSE "theater car" service was extended to Norwalk December 6, 1903. Large crowds boarded special cars for a swift ride straight to the theaters' doors. Coffee, snacks, jovial card games, and even music from mandolin players or grammophones were all part of the luxury service. At 11:00 PM, the car was ready to return the playhouse patrons to their hometowns to the west. The time from Cleveland to Norwalk was two hours. The LSE was racing toward full bloom itself. Due partially to the hastily built track between Lorain and Norwalk, running time of the first first Cleveland-Toledo cars could generously be described as torpid. In early 1902 the one way trip took anywhere from six to ten hours, depending on conditions and circumstances, and required a car change at Norwalk. After extensive improvements to the track, through service began August 18, 1902, with a scheduled time of six hours and no change of cars. A few months later the LSE began setting speed records significantly faster than the workaday schedules. On November 13, 1902, the Fraternal Order of Eagles chartered a car to carry a delegation of fifty-five men from Toledo to Cleveland. The LSE made sure a few members of the press accompanied them as the powerful car number 4 covered the one hundred twenty miles in three hours forty-eight minutes. The return trip departed Cleveland at 3:00 AM the next morning, and was handled by car 18, dubbed "The Yellow Flyer," which took only three hours twenty-two minutes. (As late as 1904, most LSE cars were still painted in the old TF&N yellow, hence the nickname of car 18.) Although the distance was slightly longer than the route of the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad, the electric was marginally faster than the steam train. These speed trials were excellent, and much needed, publicity, as the LSE was still in the hands of a bankers committee due to Everett-Moore's financial "embarrassment." By June 1903 the record had fallen further, and the scheduled travel time of LSE limiteds was changed to four hours forty-five minutes. The Norwalk Race The LSE's rival was not to be outdone, however. The various lines of the Pomeroy syndicate, including the Cleveland, Elyria & Western and Norwalk Gas & Electric, were consolidated as the Cleveland Southwestern Traction Company in February 1903, which immediately set after its own speed records. A head-to-head race was inevitable, and the opportunity came on Sunday, December 6, 1903. That morning the LSE was running an excursion car from Fremont to Cleveland, while the Norwalk Elks had chartered a Southwestern car to Cleveland. The railways had quietly hinted they would indulge in a competition, and both employees and the public waited anxiously. Southwestern car 103, a fast new Kuhlman under the command of "Speedy Bill" Kerns, was ready to depart when the LSE car arrived from Fremont. Both set off from Norwalk at the same time, and once outside the city, sped off at top speed. People along both routes knew of the race and hundreds turned out to see the cars flash by. Southwestern management had cleared the track of other traffic to give themselves every advantage, but the LSE car pulled ahead to an early lead. Then, somewhere between Vermilion and Lorain, the trolley pole became ensnared and pulled down a section of overhead wire. The car was stranded for an hour and thirty-five minutes while repairs were made. The Southwestern took the honors, arriving in Cleveland with a time of one hour twenty-nine minutes. Excluding the delay, however, the LSE car actually covered the distance eight minutes faster. Rumors spread that the LSE would make an effort to regain the title with another speed test, but it seems the LSE decided the publicity had served its purpose. President Warren Bicknell stated, "There is no foundation to the rumor. It seems to me to be poor policy to tie up an entire railroad to get a single car through ahead of schedule time. I feel that we can reduce this time when we should desire, and in case of preparing, with the best of power, equipment and track precautions, such as having men stationed at all switches and crossings, I feel that we can even reduce our time to one hour even. We are trying not to produce a record-breaking road for one trip, but one that will carry the people through on good time on all occasions." Despite such record times, limiteds from Norwalk to Cleveland still ran two hours twenty minutes on the Southwestern and two hours five minutes on the LSE. Fifth Interurban It was during this period of progress and optimism that Norwalk welcomed its fifth electric interurban. The Sandusky, Norwalk & Mansfield Electric Railway was chartered by a trio of laywers from Toledo, Cleveland, and Norwalk. Originally there were grand, if vague, dreams of being the first link in a vast interurban system connecting Lake Erie and the Ohio River. The primary goal, however, was to build between the LSE at Norwalk, and the Mansfield Railway Light & Power Company at Shelby, Ohio. Through service over the three lines could then connect Mansfield with Sandusky. The majority of the stock was sold to property owners along the route, with the people of North Fairfield being especially generous. Construction began in June 1904 and by summer 1905 the line was completed to the village of Plymouth and a branch to Chicago Junction (now the town of Willard.) Construction from Plymouth to Shelby was delayed for a year until additional funds were raised. The LSE saw the Sandusky, Norwalk & Mansfield's potential as a feeder line and provided a considerable amount of assistance. Power for the new railway was provided via a high tension line from the LSE substation at Monroeville to the SN&M substations at North Fairfield and Plymouth. An LSE line car and crew was loaned to install the overhead wire, while the SN&M's five new Niles coaches received their motors and electrical controls at the LSE Sandusky shops. LSE motorman James Trimmer and conductor Bert Thomas, both North Fairfield natives, were sent to work on the new railway, which opened July 4, 1905. Passenger facilities at Norwalk were shared with the LSE, and SN&M cars were turned on the LSE wye at Main and Whittlesey. This required a complicated series of switchbacks, and the SN&M paid 12½ cents per car to the LSE for the privilege - a small amount that added up to roughly $600 per year. By 1909, the SN&M installed their own wye at Benedict and Main eliminate the extra cost and inefficiency. Excursions and charters from Plymouth (then the southern terminus) to Sandusky began at least as early as summer 1906. These runs used LSE equipment operated by SN&M crews. LSE cars were also loaned to the SN&M at various other times, as evidenced by a photo of LSE 60 at Chicago Junction around 1906. Reportedly, the LSE even negotiated to purchase the SN&M in early 1907. If true, nothing came of the discussion and the SN&M remained an independent property its entire existence. Tragedy and Grief This era of prosperity and good feelings was not all summer excursions and profit, however. It was also marred by terrible tragedy and somber grief. The LSE had been fortunate that despite several injurious accidents, no passenger had ever been killed on an LSE car. But the law of averages caught up with the LSE in horrific fashion on June 2, 1904, in what became known as the Wells Corners wreck. That afernoon, car 66, a Toledo-Cleveland limited, arrived in Norwalk on its usual schedule. It departed on time at 4:25 PM, with sixty passengers on board. Motorman Miles Beebe and conductor K.D. Hawkins were in charge with orders to run through to Berlin Heights without stopping. Upon reaching the private right-of-way and turning off the street, Beebe opened up the controller. Soon the car was speeding through the pleasant rural scenery at 55 miles per hour. Unknown to the crew of the limited, a westbound Electric Package Agency combine had departed the Berlin Heights station several minutes earlier. (The exact number of the car is a matter of conjecture, but it appears to have been a former Lorain & Cleveland Brill.) The car was operating as an extra, and thus did not have specific orders beyond staying out of the way of the scheduled cars. Motorman George Sturgeon and conductor William Koons were aware that an eastbound limited was due and planned to let it pass at a siding near stop 173. They had nine minutes to reach the siding six miles distant, yet their car's gearing allowed a top speed of only 45 miles per hour. As the car crossed the bridge over the public highway and Rattlesnake Creek, conductor Koons checked his watch. He believed they still had two minutes in which to reach the siding only a short distance away. The tracks curved as they ascended a small hill next to an apple orchard which obstructed the view ahead. Suddenly, the onrushing limited came into sight. Realizing that disaster was imminent, both motormen cut the power and threw the brakes into emergency. But with a closing speed of 100 miles per hour there simply wasn't enough time or space for the cars to stop. Motorman Beebe of the limited saved himself by jumping from the cab of his car. The few passengers who saw the impending danger had no chance of escape. When the cars collided the EPA combine climbed over the bumper of the limited, and tore through two thirds of its wooden body as if it were tissue paper. Six men in the forward smoking compartment of the limited were killed instantly. Three had attempted to climb out windows just before the impact. After the wreck their lifeless bodies hung from the windows to the horror of the survivors. Nineteen other passengers on the limited were injured, many severely. Passengers on the combine were traumatized, but the only person seriously injured was motorman Sturgeon, who had stayed at his post. Local farmers were the first to respond to the scene, having heard the thunderous crash. One of the railway employees walked to the siding and used the dispatching telephone to call Furman Stout at his office in Norwalk. Doctors and rescuers were rushed to the scene on the Norwalk city car. The injured were taken to the St. Charles Hotel on West Main Street where one floor became a makeshift hospital ward. The dead were quietly transferred to undertakers wagons at Aillings Corners to avoid the crowd of onlookers in town. With all the passengers attended to, a work gang was sent to clear the wreckage of the cars, which had smashed together so tightly that it took several hours to separate them and clear the tracks for regular traffic. The coroner's inquest heard testimony from all train crews involved, as well as dispatchers, passengers, and Furman Stout. The investigation closed on June 10, and the verdict issued on June 15. Blame was placed on the crew of the westbound express car for exhibiting "gross carelessness and negligence" in failing to abide by general operating rule 148, which states that extra cars must clear the track for regular cars by at least five minutes. Although this was the first fatal accident on the LSE, it was not without precedent and should have been foreseen. A baggage car and passenger coach had collided near Norwalk on October 4, 1902, and a similar, albeit far less destructive, collision between a limited and a local had occurred near Wells Corner on February 1, 1904. Such accidents were probably the major motivating factor for Stout to compile a new rule book in November 1906. The books were distributed to all employees of the line and sized to fit in a vest pocket, readily available for reference whenever needed. The rule book may have helped avoid some dangerous situations, or to place blame more easily on an employee who did not follow the book, but the risks inherent in running cars in both directions on an unsignaled single-track could never be completely eliminated. On July 3, 1908, the crew on work car 402 forgot that a limited was due, resulting in a relatively minor collision at Norwalk's west city limit. Eight passengers were injured, including two LSE officials riding on the limited. An accident on September 4, 1910 was nearly an exact repeat of the Wells Corner wreck. Twenty-six passengers were injured, nine seriously, when a motorman forgot his orders and ran his eastbound limited into a westbound local just east of the city. September 1907 brought a very personal loss which left everyone on the LSE griefstricken. Furman Stout fell suddenly ill during a trip to Toledo and was hospitalized there on August 20. He underwent surgery for gallstones, but developed blood poisoning and never recovered. He died on September 14 at age 48, with his wife and mother at his bedside. Stout was loved by all the LSE employees and management for his perpetually cheerful personality and the respect and compassion he showed for all the men. He was known to possess a remarkable ability for remembering names and faces, and knew and addressed every man under him by his given name. He believed strongly in discipline and responsibility, but always strived to bring out the best in his workers by encouraging their sense of honor and making them feel they were a member of a family. It is said that he seldom suspended or discharged a man for misconduct, and selflessly recommended good men to positions on other railways when he saw the advancement was in their best interest. He had the sincere respect of not only the train crews and management of the LSE, but of many others in the interurban and steam railroad industry. The funeral was held at his home in Norwalk on September 17, and is said to have been the largest display of mourning the city's history. Floral arrangements were sent by the Masons, Elks, the Central Electric Railway Association, and his many friends. On the morning of the funeral, special cars brought LSE president Edward Moore and the office staff from Cleveland, and officials of other electric and steam railroads from Toledo. The Fremont car shops were closed and arrangements made to allow as much as half of all LSE operating staff to pay their respects in person. After the ceremony, Stout's casket was placed on a special car fitted with black drapes and taken to Detroit for burial. The LSE lost one of its great leaders, a man who began at the bottom of a steam railroad and rose to the position of top manager on possibly the greatest electric railway of the interurban era. He made the TF&N operate smoothly and efficiently, and oversaw efforts to improve the entire LSE system to the same high standards. Management was again undergoing changes. Less than four months before his death, Stout had promoted Lewis K. Burge from superintendent of the Sandusky division to general superintendent of the entire railway. Burge made his home at 39 West Seminary Street in Norwalk. Fred Coen was promoted from secretary and treasurer to succeed Stout as general manager on October 28, 1907 - thirteen years after he was first appointed secretary of the fledgling Sandusky, Milan & Norwalk Electric Railway. Coen continued to live with his family in Lakewood and commuted to the LSE offices daily. The following year he was elected vice-president of the LSE, in addition to his duties as general manager. |

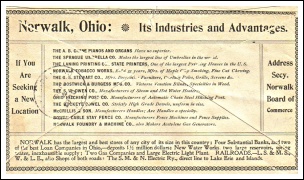

dated August 1900, touts the city's business and industry. (Drew Penfield) |

symbol of Norwalk's growth, prosperity, and promising future. (Drew Penfield) |

|

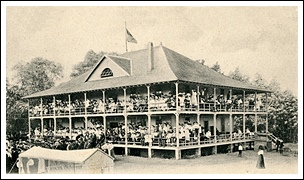

Brook Park proves what a popular recreational spot it was. (Drew Penfield) |

|

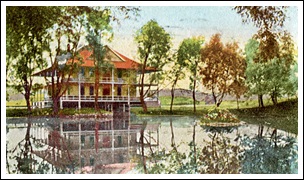

the lake and pavilion at Willow Brook Park. (Drew Penfield) |

|

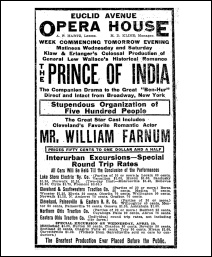

which lists fares for the LSE theater car. (Plain Dealer) |

|

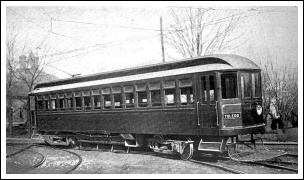

used it for high speed tests between Toledo and Norwalk in 1902. Click to open article. (Street Railway Journal) |

|

Cleveland on November 13 and 14, 1902. (Plain Dealer) |

|

wire failure, but was still capable of faster speeds than the CSW. (Plain Dealer) |

|

declared "an important date in the history of Norwalk" by the newspaper. (Norwalk Reflector) |

|

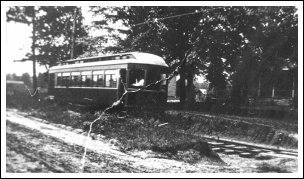

between Norwalk and North Fairfiled. Note that the track was not yet ballasted. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

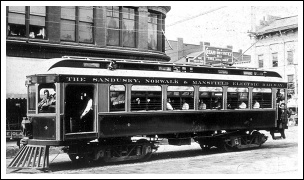

in front of the glass block in the railway's early days. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

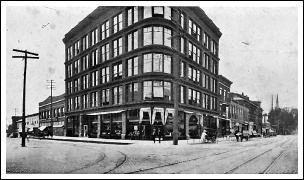

Benedict Ave. is visible at left in this photo of the Glass Block. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

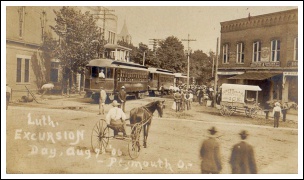

board a trio of LSE Barney & Smith cars at Plymouth, Ohio on August 7, 1906. (Drew Penfield) |

|

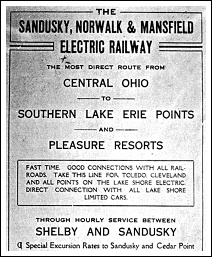

Cedar Point and connections with the LSE. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

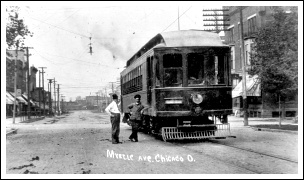

Ave. in Chicago Junction (now Willard) circa 1906. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

foreshadowed the disaster to come. (Norwalk Reflector) |

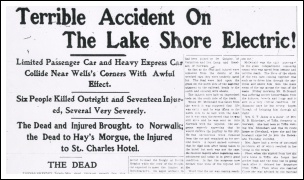

few miles east of Norwalk near Wells Road on the afternoon of June 2, 1904. (Norwalk Reflector) |

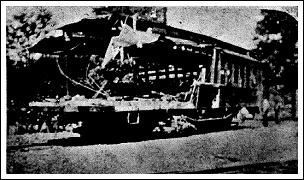

limited car (right) has been demolished in the collision. (Dennis Lamont) |

from the scene of the wreck. (Dennis Lamont) |

six men sitting in the forward smoking compartment were killed. (Ralph A. Perkin photo) |

for the victims of the Wells Corners accident. (Dennis Lamont) |

checked his watch just before the accident occurred. (Dennis Lamont) |

Pole line follows curve of the LSE. An orchard inside the curve obscured view of the cars. (Dennis Lamont photo) |

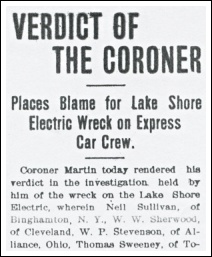

was responsible for causing the accident. (Norwalk Reflector) |

(Drew Penfield) |

city limits on July 3, 1908. (Dennis Lamont) |

that injured eight passengers. (Norwalk Reflector) |

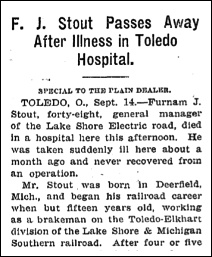

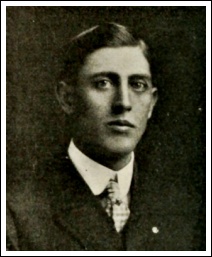

after an operation in a Toledo hospital. (Plain Dealer) |

casket to Detroit where he was buried September 18, 1907. (Norwalk Reflector) |

to general superintendent of the entire LSE in May 1907. (Electric Railway Review) |

general manager of the LSE at Norwalk. He was promoted October 28, 1907. (Electric Railway Review) |

|

|

|