|

The Sandusky, Milan & Norwalk remained the only electric railway serving Norwalk for several years - although no less than five others were proposed in the decade after the SM&H was chartered. Only one of the five, the Sandusky, Monroeville, Bellevue & Norwalk, ever came close to reality. In those early, heady days of the interurban era, new railways were incorporated, promoted, and folded quickly. Most never progressed beyond lines on a map. Eventually, one new railway did succeed, and it came not from Sandusky or the Cleveland syndicates, but from three Michigan interurban promoters: James Dudley Hawks, Samuel Floyd Angus, and Henry Allyn Haigh. James Hawks was a highly experienced railroad man, having started his career with the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad, and served as chief engineer of the Michigan Central Railroad for many years. He then became a street railway manager in Detroit, transforming horse-car lines into the city's first electric lines. Samuel Angus was a native of Wood County, Ohio, where he had been a schoolteacher before becoming a businessman. Eventually he rose to be the Michigan manager for the New England Mutual insurance company at Detroit, and began investing his wealth in electric railways. Henry Haigh was a prominent Detroit lawyer who became associated with Hawks and Angus in 1898 when he helped secure right-of-way for the Detroit, Ypsilanti, Ann Arbor & Jackson electric railway. When that line was completed, the three men continued their partnership and began searching for their next venture. The Cleveland interurbans of the competing Everett-Moore and Pomeroy-Mandelbaum syndicates were slowly reaching west, but unlikely to reach Toledo for a number of years. The opportunity was ripe for a railway to build east from Toledo and meet the Cleveland lines at an intermediate point. Norwalk was chosen after considering its size, economy, and the proposed extensions of the Cleveland lines. Samuel Angus visited Norwalk on April 6, 1899, to scout the territory and meet with business leaders of the city, who embraced the idea of another interurban. Nine days later the promoters sent a letter to their Norwalk contacts (among whom was former SM&N director S.E. Crawford) instructing them to begin securing right-of-way between Bellevue and Norwalk, the last of which was obtained April 24. Surveying of the route was done in July. Financial backing for the railway came from the Comstock family of Alpena, Michigan. Andrew Westbrook Comstock was born in Port Huron in 1838, and made his fortune in the Michigan lumber industry before moving into banking and politics. He was also Henry Haigh's father-in-law, and had previous business connections with James Hawks and Samuel Angus. Andrew's brother, William B. Comstock, and William's son, William Alfred Comstock (who became governor of Michigan in 1933), were also partners. The Comstock Construction Company was incorporated in early September 1899, and contracts were immediately let for construction of the roadbed, powerhouse, and substations. The Toledo, Fremont & Norwalk Railroad Company itself was incorporated September 12, 1899, with Samuel Angus president, William B. Comstock vice-president, William A. Comstock secretary, Andrew W. Comstock treasurer, and Henry Haigh general counsel and assistant treasurer. Another Michigan native who was an important figure in the TF&N, the LSE, and Norwalk, was Furman Joshua Stout. Born in Deerfield in 1858, Stout began his railroad career at age 15 as a brakeman (a notoriously dangerous job) on the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern. He rose through the ranks steadily, eventually becoming yard master at Toledo. In 1893 he moved to the Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad, serving as superintendent at Toledo, then Norwalk, and finally Massillion. Stout was close friends with Samuel Angus, probably meeting during their years on the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern. It was Angus who lured Stout away from the W&LE with an offer to become general manager of the TF&N in May 1900. Given the background of James Hawks and Furman Stout, it's not surprising that the TF&N was built to the highest standards then in use by steam railroads. The roadbed was substantial, rails heavy, bridges made of steel and concrete, and the rolling stock rugged. For safety, state-of-the-art, electric, interlocking derails and signals were installed at all grade crossings with steam railroads. Incorporation of the TF&N spurred both the Everett-Moore and Pomeroy-Mandelbaum syndicates to push their respective railways to Norwalk as quickly as possible. The first line to connect with the TF&N would reap most of the benefits and profits. All expectations were on Pomeroy-Mandelbaum's Cleveland, Elyria & Western railway, which was then in operation as far west as Oberlin. As early as April 1900, Fred Pomeroy and Henry Haigh had met in Cleveland to discuss a connection of the two lines, but no agreement was made at the time. The Norwalk Gas & Electric Company, also incorporated in April 1900 and closely aligned with the Pomeroy syndicate, was tasked to build a twenty-two mile extension between Oberlin and Norwalk. A franchise was granted by Erie County in January 1901, Huron County in February, and track-laying began in March. Meanwhile, Everett-Moore's Sandusky & Interurban Electric Railway was still wrestling with county commissioners and village councils. Newspapers regularly talked of the TF&N-CE&W connection as a fait accompli, despite the fact that the CE&W did not yet have any service west of Oberlin and the TF&N was operating only as far east as Monroeville. Construction on the TF&N progressed rapidly, however. Grading of the roadbed between Monroeville and Norwalk, following the Bellevue-Norwalk Road (present day US 20) was already underway by the time Monroeville service began in January 1901. Work was delayed slightly when the Huron County Commissioners obtained an injunction due to the railway not building on the exact location the county had specified. A compromise was soon reached and work resumed January 11. Another delay occurred in March, when the Norwalk contractor hired to pour concrete abutments for the bridge across the Huron River filed suit against the TF&N for non-payment of $1000, and demanded that the 76-foot steel bridge be sold to pay the debt. Work was halted when the local constable siezed a quantity of rails and ties, but the matter was apparently settled quickly and the bridge completed on April 19, 1901. From the bridge the TF&N tracks ascended the hill to West Main Street and connected to the SM&N track. The very first TF&N car to reach Norwalk was passenger car 11, under the command of William B. Comstock and motorman Sam Franks. It arrived at 4:15 PM on April 21, 1901 pushing a flat car loaded with trolley wire and construction equipment. There was no ceremony and the visit was brief. The motor car was turned on the wye at Whittlesey Ave., the flat car was re-coupled to the rear, and the train returned west. Regular service was expected to begin April 24, but a formal agreement between the TF&N and Everett-Moore for use of the West Main Street track had not been finalized. On Sunday, April 28, TF&N cars ran between Norwalk and Bellevue every hour on a temporary arrangement, and as many as 1600 Norwalk residents took the opportunity to ride the cars over at least a portion of the line. No cars ran the following two days, but regular scheduled service began May 1, 1901. One-way fares to Monroeville, Bellevue, Fremont, and Toledo, cost 10¢, 20¢, 45¢, and 85¢, respectively. Round trip fares cost double. The TF&N was a success from the start and ran like a well-oiled machine. Furnam Stout is generally credited with being the first to apply steam railroad methods of operation and management to an electric railway, which resulted in cars running consistently on schedule and without major mishaps. Stout is also likely responsible for the TF&N having a true freight service, which began on January 2, 1901, and grew steadily until it accounted for 10% of gross earnings. Within a few months those earnings had reached the rate of $200,000 per year. Despite this, there were no freight facilities at Norwalk. As was the practice in most other towns and cities at the time, freight was loaded and unloaded in the street. As an independent company, however, the TF&N was to be short lived. Although Andrew Comstock had made statements to the contrary in 1899, the likely intention all along was to sell the railway once it was fully operational and profitable. The Comstock's were not railroad men, they were financiers expecting a return on their investment. Hawks, Angus, and Haigh, were experienced railway men, but primarily they were entrepreneurs and builders. Rather than stay in Ohio operating the TF&N, they would go on to other enterprises elsewhere. Consolidation & Competition Although it was assumed that the CE&W would connect with the TF&N, their race to Norwalk against the Sandusky & Interurban was fraught with difficulties, both physical and financial. As early as January 1901 a plan was floated whereby the CE&W and S&I would enter Norwalk on a shared right-of-way, saving each company as much as $50,000 in construction costs. Fred Pomeroy suggested both railway's use the more direct CE&W right-of-way and either build and own the track jointly, or each build one half of a double-track mainline. Everett- Moore was adamant on retaining full ownership while allowing the CE&W use of their track. Neither side was willing to make concessions as each viewed the other as encroaching on their territory. Frustrated, Pomeroy stated that the CE&W would not only use their preferred route and their own franchise to enter Norwalk, but would also establish their own competing city streetcar service. Two factors eventually derailed the CE&W's plans. The first was encountered that spring when it was realized that the CE&W's planned crossing of the Vermilion River at Birmingham required a large and expensive bridge to span the four-hundred foot wide gorge. With no practical solution forthcoming, the company considered abandoning their chosen route. Finally, the Osborn Construction Company took up the challenge of building a steel arch bridge within the railway's budget. Still, the bridge was costly and time consuming to build. A mistake during construction of the bridge and striking track workers further impeded progress. Little work was accomplished on the CE&W through the summer. The second blow to the CE&W was dealt in July 1901, when Everett-Moore agreed to purchase the TF&N for $3,350,000. Although the CE&W and the S&I were perceived as racing to make the connection at Norwalk, the ultimate objective was complete ownership. Both syndicates negotiated to buy the TF&N and alternately claimed that they would instead build their own line to Toledo. This was most certainly posturing for the press, or perhaps a (rather transparent) bargaining tactic. Neither Everett-Moore nor Pomeroy were in a position to quickly build sixty miles of new railway that could hope to compete with the well-built and operated TF&N. Angus, Haigh, and the Comstocks were well aware of this. They had a price for the TF&N and they stood firm. The money and property officially changed hands on August 9. With the TF&N in the hands of their rivals and the extension to Norwalk proving more costly than anticipated, Pomeroy-Mandelbaum eventually abandoned their plans of reaching Toledo, and began to concentrate on expanding southwest of Cleveland to Mansfield, Bucyrus, and connections to Columbus. Ownership of the TF&N, however, did not mean the Lake Shore Electric was complete. The S&I had struggled against many obstacles to reach Norwalk, including franchises, a shortage of labor, a bridge contractor who skipped town without paying workers, and a physical assault on manager Thomas Wood by an outraged farmer who did not want the railway to cross his property. At the time the TF&N purchase was closed, all bridgework and grading between Berlin Heights and Norwalk was complete, but no rails were in place. With the creation of the LSE work was rushed through the fall to complete the track, which followed present State Route 61 and Gibbs Road. On November 19, 1901, city council granted a franchise for the LSE to cross Old State Road and to connect with the East Main Street track near present-day Oakwood Drive. On December 8, a cold and rainy Sunday, one of the Norwalk city cars (formerly SM&N 17, by then renumbered 4) was the first to travel the new LSE rails between Norwalk and Vermilion. The following day several trips were made between Norwalk and Lorain, but no regular schedule was instituted until a month later. LSE Makes Changes With the Lake Shore Electric in operation, several changes in and around Norwalk were made for reasons of efficiency and organization. The rosters of the newly merged railways were assessed to determine what cars were still of use and how they were to be used. Most of the SM&N cars were in decrepit condition and completely inadequate for the Lake Shore's needs. But with no other cars immediately available they remained in operation between Sandusky and Norwalk. Almost all of them were scrapped during 1902-1903. SM&N 4, the second Norwalk city car, was one of the few to survive. It was repainted, renumbered LSE 101, and continued its half-hourly trek the length of Main Street. The TF&N fleet, by contrast, consisted of more than twenty large, sturdy, coaches and freight motors built by Barney & Smith of Dayton, Ohio, all of which were less than three years old. The coaches were fifty feet long, seated sixty passengers, and featured enclosed smoking sections. These were the cars the LSE needed, and all were transferred to the LSE roster with their original numbers. Gradually they were upgraded with four 75 horsepower motors, the open rear platforms were enclosed, toilets installed, and their yellow TF&N paint scheme covered in "Big Four" orange, the new LSE standard. The LSE also planned to build a new station at Norwalk, which may have been intended as a union station for multiple interurban companies, similar to what was being planned in Cleveland at the time. A lot at 39 Whittlesey Ave., just south of the LS&MS railroad crossing, was purchased in July 1901. The Norwalk Reflector reported that a combined freight and passenger terminal, as well as offices, and possibly even car barns, was planned for the site. The original franchises for both the CE&W and the Sandusky, Monroeville, Bellevue & Norwalk, called for those railways to enter town by running south on Whittlesey and connecting to the existing track. The site on Whittelsey would have been the logical location for a single station for all three companies. A new station was also necessary to comply with the city council's demand that freight no longer be loaded or unloaded on the street. Like the planned terminal at Cleveland, however, the Norwalk terminal plans were cancelled due to Everett-Moore's financial troubles, the LSE receivership. In July 1902, Norwalk council took action on several interurban related matters. The ordinance prohibiting the handling of freight in the street was passed, and the Whittlesey Ave. franchises for both the bankrupt SMB&N and the CE&W were revoked. The CE&W gave up on much of its private right-of-way into Norwalk. Instead their track joined East Main Street at Seminary Road, about four miles outside Norwalk, then connected to the LSE track at East Main and Old State Road. As part of the agreement to use the LSE track, the two railways agreed to not engage in wasteful competition such as rate wars. The CE&W station was at 26 West Main, directly across Hester Street from the LSE station. The LSE was also granted a franchise to extend their track and install a wye into the property at 39 Whittlesey, where a small wood frame building acted as a freight depot. A year later, however, the LSE discontinued freight service in favor of express only. The depot was then used exclusively by the Electric Package Agency until freight service was resumed after World War I. The freight house siding was also used to park the city streetcar at night. A small passing siding on West Main street was extended onto East Main as far as Linwood Ave. to provide more track space for the increase in traffic from both LSE and CE&W cars. At first, management of the newly consolidated railways was left largely intact. Richard E. Danforth, superintendent of the Lorain & Cleveland railway, was appointed general manager of the entire Lake Shore Electric. On August 12, 1901, Furman Stout was named general superintendent of the LSE under Danforth. In December 1901, Samuel Angus and Henry Haigh offered Stout the position of general manager of their Michigan railways, but he declined, preferring to stay in Ohio with the railway he had helped bring to maturity. Other TF&N personel who remained with the LSE included superintendent W.B.W. Griffin, attorney Harry Rimelspach, and head dispatcher Dan Lavenberg. Thomas Wood, who had been manager of the SM&N and the Sandusky & Interurban, was made superintendent of construction, tasked with completing the Norwalk-Ceylon section. When Everett-Moore's financial situation turned dire in January 1902, however, management was downsized and streamlined. The stated reason being that the company simply had too many superintendents and managers for its size and amount of business. Thomas Wood was let go in January, and Lavenberg resigned shortly after. In April, Danforth resigned and returned to his native Buffalo, New York. Stout was promoted to replace him, and moved from Fremont to Norwalk, making his home at 52 West Main Street. The general offices of the LSE were only a block away at 24 West Main, on the second floor of the Case Block above the ticket office and waiting room. The LSE emerged from receivership in April 1903 but remained under the control of a committee of bankers. Barney Mahler stepped down as president and the position was offered to Warren Bicknell, general manager of the Aurora, Elgin & Chicago railway, and an associate of the Pomeroy-Mandelbaum syndicate. Bicknell moved to Cleveland and assumed his new duties August 1, 1903. |

three Michigan railway builders who conceived the Toledo, Fremont & Norwalk in 1899. (Drew Penfield) |

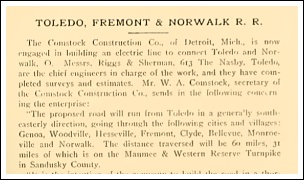

struction Co. in September 1899 to begin building the TF&N three months before the railroad itself was incorporated. (Street Railway Review) |

|

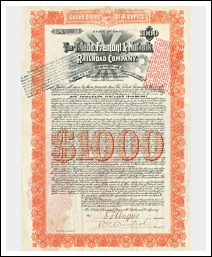

both the Comstock Construction Co. and the TF&N Railway at age 18. (National Archives) |

|

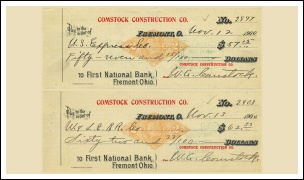

written in 1900 during construction of the TF&N and signed by William A. Comstock. (Drew Penfield) |

|

1900 and signed by Samuel Angus and Andrew Comstock. (Drew Penfield) |

|

extensive steam railroad experience played a major role in making the TF&N a well-built and well-run interurban. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

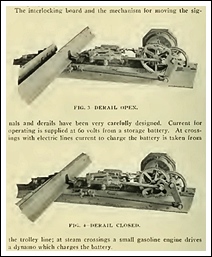

used by the TF&N at railroad crossings. (Street Railway Review) |

|

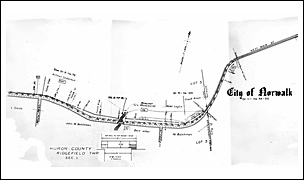

Bellevue-Norwalk Road, across the Huron River, and up to the SM&N on West Main Street. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

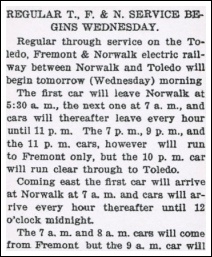

service to and from Norwalk, including schedule and fares. (Norwalk Reflector) |

|

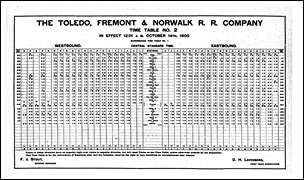

Toledo was open only as far as Bellevue at that time. (Street Railway Review) |

|

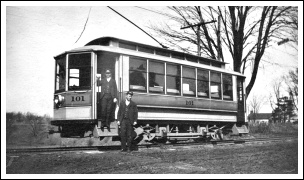

ex-TF&N Barney & Smith car on Main Street from the early LSE days is as close as one gets. (Drew Penfield) |

|

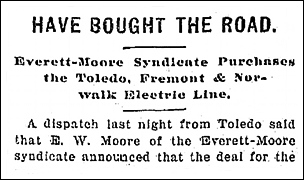

made final on August 9, 1901. (Plain Dealer) |

|

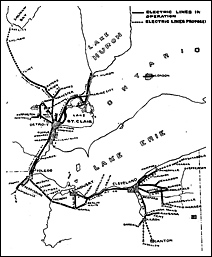

interurban empire stretched from Akron, Ohio to Flint, Michigan. (Electrical World and Engineer) |

|

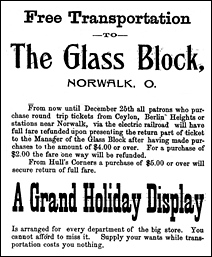

fare for shoppers who rode the new LSE to Norwalk in December 1901. (Erie County Reporter) |

|

syndicate that controlled the CE&W and was the main rival of Everett-Moore and the Lake Shore Electric. (Drew Penfield) |

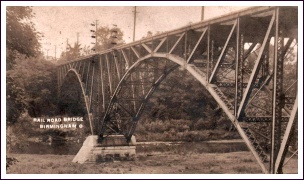

arch bridge over the Vermilion River at Birmingham. (Drew Penfield) |

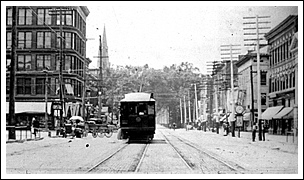

State Road, in front of the Sprague Umbrella Company. (Dennis Lamont) |

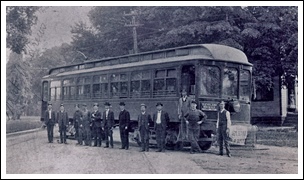

junction at East Main and Old State Road. Curiously the car is turned toward the SM&N track. (Drew Penfield) |

the end of the local car route on West Main Street. (Dennis Lamont) |

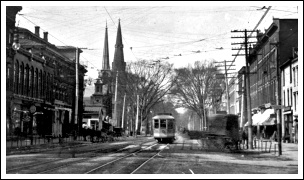

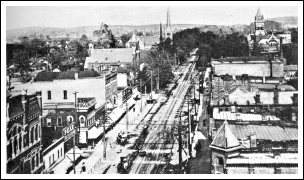

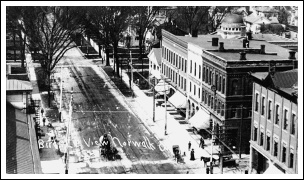

View is west from Whittlesey Ave. (Dennis Lamont) |

The original 1902 building is in the foreground. (Dennis Lamont) |

LSE 8, a former TF&N car, near the Whittlesey Ave. freight house. LS&MS railroad crossing in background. (Drew Penfield) |

house wye toward the Glass Block as an LSE car approaches. (Drew Penfield) |

loading platform at 39 Whittlesey, just north of Monroe. (Drew Penfield) |

passing siding extended to the Linwood Ave. intersection. (Dennis Lamont) |

extended Main Street passing siding. (Dennis Lamont) |

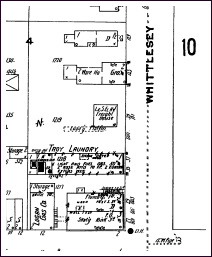

all visible in this view. (open to see labels) (Dennis Lamont) |

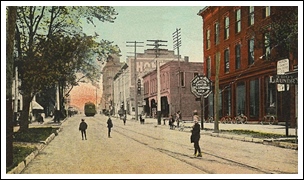

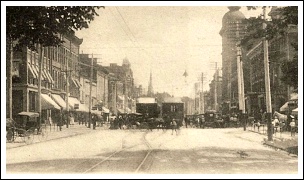

by townspeople and horse-drawn buggies. (Drew Penfield) |

Lorain & Cleveland, became general manager of the LSE in 1901. (Street Railway Journal) |

Aurora, Elgin & Chicago, became president of the LSE in 1903. (Drew Penfield) |

|

|

|